Flutter DDD

Keeping your code clean and testing it are the two most important development practices. With Flutter, this is even more true than with other frameworks. On the one hand, it's fun to tinker with a quick application, on the other hand, larger projects start to fall apart when you mix business logic everywhere. Even state management models like BLoC are not sufficient by themselves to allow for an easily extensible code base.

The Secret to Maintainable Apps

This is where we can employ clean architecture and test driven development. As proposed by our friendly Uncle Bob, we should all strive to separate code into independent layers and depend on abstractions rather than concrete implementations.

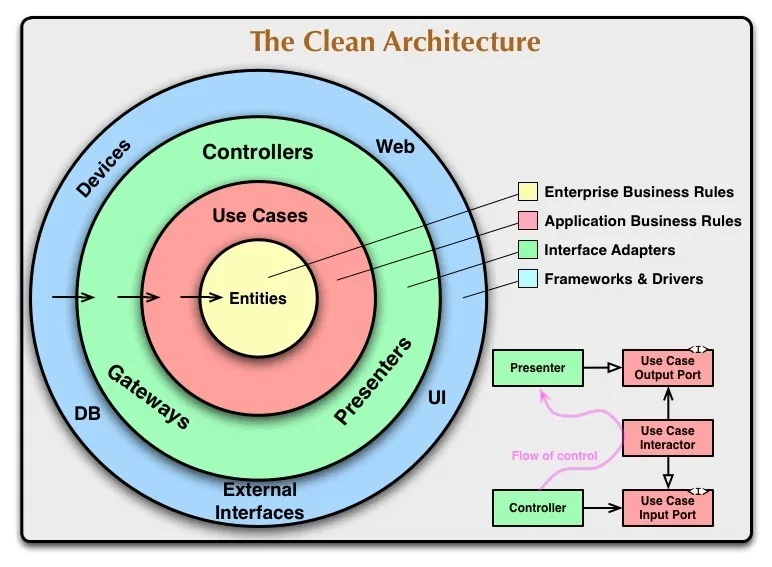

How do you achieve such independence? Although we are getting a little ahead of ourselves, in the layered "onion" image below, the horizontal arrows ---> represent the flow of dependency. For example, Entities are not dependent on anything, Use Cases are only dependent on Entities, etc.

Uncle Bob's Clean Architecture Proposal

All this is, well, a bit *abstract (pun intended)*. Also, while the essence of a clean architecture remains the same for each framework, the devil is in the details. Principles like SOLID and YAGNI sound nice, you may even understand what they mean, but it won't do you any good if you don't know how to start writing clean code.

Clean Architecture & Flutter

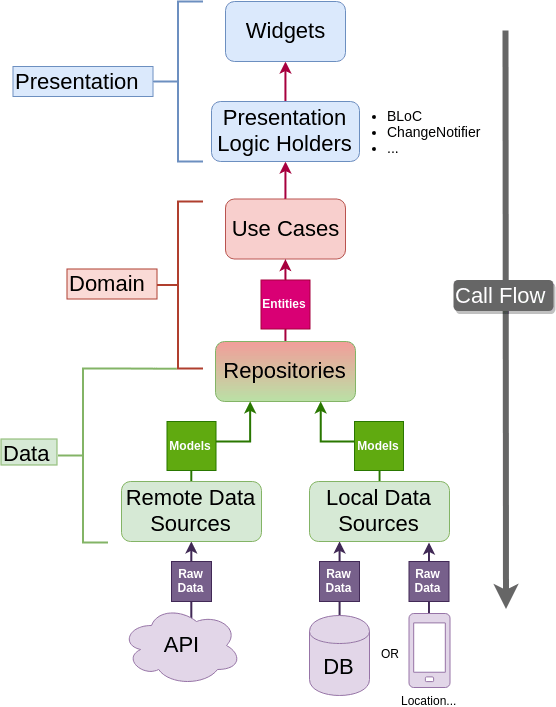

This is only a high-level overview which may or may not tell you much, depending on your previous experience. We will dissect and apply this diagram to our social media App in a short while.

Explanation & Project Organization

Each "feature" of the application, such as getting interesting information about a number, will be divided into three layers: presentation, domain and data. The application we are building will have only one feature.

To make creating individual feature folders easier, you can use this VS Code extension.

Presentation

This is the kind of thing you are used to in the "impure" architecture of Flutter. You obviously need widgets to display something on the screen. These widgets then dispatch events to the Block and listen for status (or an equivalent if you don't use the Block for status management).

Note that the "Presentation Logic Holder" (e.g. Bloc) doesn't do much by itself. It delegates all its work to use cases. At most, the presentation layer handles basic input conversion and validation.

Domain

Domain is the inner layer which shouldn't be susceptible to the whims of changing data sources or porting our app to Angular Dart. It will contain only the core business logic (*use cases*) and business objects (*entities*). It should be totally independent of every other layer.

But... How is the domain layer completely independent when it gets data from a Repository, which is from the data layer? Do you see that fancy colorful gradient for the Repository? That signifies that it belongs to both layers at the same time. We can accomplish this with dependency inversion.

That's just a fancy way of saying that we create an abstract Repository class defining a contract of what the Repository must do - this goes into the domain layer. We then depend on the Repository "contract" defined in domain, knowing that the actual implementation of the Repository in the data layer will fulfill this contract.

Dependency inversion principle is the last of the SOLID principles. It basically states that the boundaries between layers should be handled with interfaces (abstract classes in Dart).

Data

The data layer consists of a Repository implementation (the contract comes from the domain layer) and data sources - one is usually for getting remote (API) data and the other for caching that data. Repository is where you decide if you return fresh or cached data, when to cache it and so on.

You may notice that data sources don't return Entities but rather Models. The reason behind this is that transforming raw data (e.g JSON) into Dart objects requires some JSON conversion code. We don't want this JSON-specific code inside the domain Entities - what if we decide to switch to XML?

Therefore, we create Model classes which extend Entities and add some specific functionality (toJson, fromJson) or additional fields, like database ID, for example.